Despite living in a society that cultivates an indoor culture of TV, DVD, and video games, I was lucky enough to have been brought up in an environment where the emphasis was put on physical training. Due to my family background in martial arts, the training could be called martial. Specifically, I was—and still am—being trained in a Japanese battlefield martial tradition, but along the way, I have been exposed to the weapons and fighting systems of other cultures, both classical and modern. That background has formed the basis of my understanding of the martial man and the meaning of his endeavors. It has become one of the core reference points by which I compare the fighting arts of other cultures.

To further expand my outlook on the combative aspects of cultures around the world, a few years ago my father suggested that I begin assisting him and Nick Nibler in their work in law enforcement training. Through that experience I got not only a personalized education on the curriculum they were teaching through the ICS, but also a firsthand view of law enforcement’s approach to personal combat. As I grew older, my father began bringing me along on trips to assist in ICS training courses with the Marine Corps’ MCMAP program and for 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, USMC. The men of the United States Marine Corps provided me important and interesting insights on the mentality, lifestyle, and duty of the modern warrior.

Early this year, my father and I were again privileged to work with 3rd Recon in Okinawa, where we gave two Stalker courses. We spent three weeks training with these highly motivated, extremely competent men. During the three weeks of intense training, I observed key attributes of these Marines that illustrate the distinction between warriors and soldiers. The aspects that mark the distinction between soldiers and warriors can be put into two areas that are at the root of their professionalism: capability and responsibility. Every morning when we drove into the camp at about 0720, Marines were already engaged in their unit training. To our right there was a Marine playing the role of a yelling, street thug, as two Marines diplomatically approached him with their rifles at low-ready; further down the road, twenty Marines were jogging in formation; in the left lane, a convoy of Humvees traveled down the road. As we drove down the street, we often found ourselves in the imaginary crossfire of a simulated firefight between Marines on the right and the enemy on the left. One morning in class, my father asked the Marines we were working with if they ever went out and did extra supplemental training on their own. All the men in the room said yes; all of these men, dedicated to their profession, went beyond the demands of their required daily training with their units and did even more training on their own.

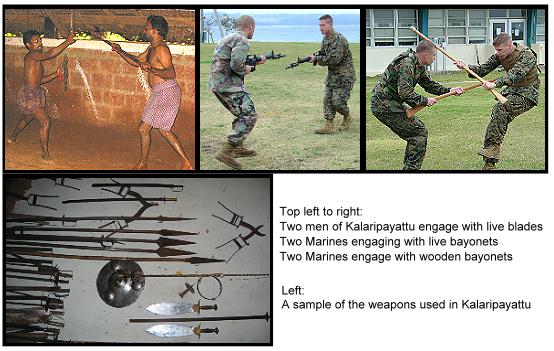

As part of the curriculum of the Stalker package, trainees learn how to move efficiently under the stress of facing a weapon-wielding adversary. They engage in short drills in which they must dominate an opponent who is armed with anything from empty hands to a short blade to a rifle-and-bayonet. A senior Marine or instructor plays the "enemy," who, with full intent and aggression, thrusts or slashes at the Marine. The Marine closes the distance and, with whatever weapon he has, subdues and dominates the "bad guy." Most often, the drills are done with wooden rifles with rubber tips simulating a rifle with a bayonet, and wooden knives in place of live blades. Still, there are plenty of bruises and minor injuries. This training is stressful and dangerous for both sides, but it is absolutely necessary, as it requires a combative intent directly applicable to real combat. The more stress, the better the preparation for real combat.

To increase the neural intensity of the training, by the third day of the course, live bayonets and blades are used. Where there would normally be contact with live blades in an engagement, the Marine stops his thrust within fractions of an inch from the target on his enemy. This training is not done slowly, but, if anything, is even faster, owing to spikes in adrenaline. It requires extreme trust on both sides. Doing live blade training requires professionalism and combative intent, as displayed expertly by the Marines of 3rd Recon. It was obvious that the Marines take this training seriously; there was absolutely no "playing around" during this training. This sort of live blade training would frighten most people, but the Marines we worked with were all willing and excited to train with a risk level not common in their normal training.

It was apparent that as important as they take their responsibilities in the skill training needed as modern military men, the Marines we worked with have, as well, a thorough understanding of their responsibilities as warriors. They are compassionate concerning life, passionate in their profession, and viciously proficient in the execution of duties in the protection of this country. I was very fortunate to be allowed to learn so much from the 3rd Recon Marines in Okinawa. This trip gave me the opportunity to get an intense tutorial on what it means to be a Marine warrior.

In contrast to modern military training, during the summer of 2003 I was able to get a glimpse of combative culture at the other end of the historical continuum. In June and July I accompanied my father on a hoplological research trip to southern India. There we investigated classical fighting arts of Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. We visited many sacred kalari (training halls), interviewed knowledgeable gurukkals, and photographed and documented evolving and dying fighting traditions.

One of the most fascinating of the martial traditions and teachers was a particular tradition employed at a school of Kalaripayattu located in Kaduthuruthi in the state of Kerala. We spent a few days learning from and about Vasudewan Gurukkal, the teacher of the tradition, who demonstrated and explained his style of Kalaripayattu. While none of the men who trained at Vasudewan Gurukkal’s kalari were particularly large or strong, they were impressively athletic. To me, it appeared that they were not training for sport or entertainment, but for combat. This was an important distinction between their training and many of the other schools we encountered in India. One primary factor indicated that they were training in a combat fighting art: the almost exclusive use of weapons in their adversary training. In Vasudewan Gurukkal’s Kalari we witnessed two men doing a prearranged pattern of strikes and disruptions against each other with their swords or spears and shields. Often, they would use swords or spears with live blades. Because the use of live blades more closely simulates real combat, the implication arises that this tradition was combatively oriented, rather than sport-driven. The little historical background we could find on Kalaripayattu seemed to indicate that Kalaripayattu was likely not primarily a system of battlefield combat, but rather a combative tradition created for organized dueling on state level.

In a side-by-side look at the classical fighting traditions of southern India and the Marine Corps, one finds certain common principles that define the warriors of both. These principles are likely integral to other combative cultures as well. I became aware that in the combative cultures of both the traditional southern Indian martial artists and the Marine Corps, there is the requirement that the constituents have the ability to fight and, just as important, are knowledgeable of the appropriate time for and responsibilities that come with fighting. They train for reasons that ultimately come from within and fight for reasons dictated by necessity and social responsibility. Similarly, with the Marines I met in Okinawa, ethics played a huge role in their identity as warriors. A moral system produces a cohesion and continuity within the team and professionalism in the execution of their work.

As well as parallels with the combative cultures in south India, the Marines I worked with in Okinawa had a sense of morality that also seemed to share concepts with Japanese bushido. The differences between these two Asian cultures, though, are prominent, and are likely a result of cultural evolution. This is an area that I hope to explore in further research. In addition to similarities between the classical fighting arts of southern India and modern combative arts of the U.S. Marine Corps, I am beginning to see important principles that form the foundations in the purpose of the armed professional in many cultures.

Studying these cultures as objectively as possible, as an outsider I am able to learn from a unique angle that a member of either culture likely could not. I believe this position allows me to observe different cultures with less bias and broader perspective. Of course, I don’t have the appropriate perspective to say what it ultimately means to be a Marine or an Indian duelist, but with the perspective that I have, based on what I’ve learned during my few years of training and education, I can’t help but attempt to infer what it means to be a warrior.